Day of DH 2014

One of the uses of Digital Humanities is to enlarge the community of scholars. Building up to a paper at the annual German Studies Association conference in September, I will be researching how the Open Source model of creating software and hardware can be applied to the humanities. Specifically, what does having open access to information and scholarship do to/for/with that information and scholarship. One mantra in Open Source software development is that many eyes on the code spot the errors more quickly. I would like to repurpose that mantra for humanities, specifically history: many eyes make more better history.

To try an experiment, here is a section of chapter one of the dissertation. A quick look at the use of air power as it changed from WWI to WWII and the use of strategic bombing in WWII. Any and all comments on the process, the information, scholarship, history, images, methodology, layout, facts, etc are welcome and acceptable.

STRATEGIC USE OF AIR POWER IN WWI AND WWII

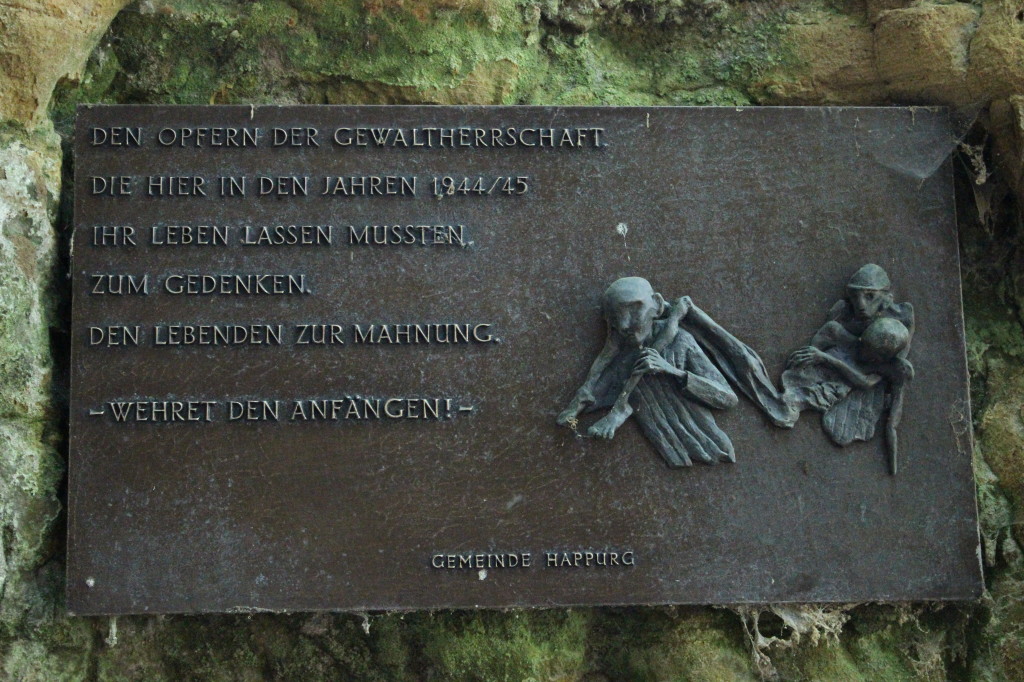

By some accounts, the total Allied air offensives during World War II dropped almost two million tons of bombs on Germany, completely destroying over sixty cities, killing an estimated 583,000 Germans as well as 80,000 Allied air crew. [ref]Hansen, Randall. Fire and Fury. Doubleday Canada, Limited, 2009, 279.[/ref] What was the goal of strategic bombing? Did the bombing of British or German cities really have the desired effect? Beginning with their implementation in World War I, airplanes were believed by only a few military leaders at the time to be of any strategic advantage in modern warfare. Incorporating strategic use of airplanes in wartime planning was in itself an early battle fought among US military leaders even before Germany invaded Poland. This section will describe the early use of bombing and how it came to be used strategically in World War II by both Germany and the Allies. Weakening civilian morale and destroying military production facilities were the main goals for both sides of the conflict. This section will look at these two goals, and describe the success or failure of the goals as seen by contemporary observations as well as present-day arguments. Finally, Big Week is discussed as a major turning point in German military planning, effectively cementing the turn from offensive to defensive measures.

Bombing as Strategy

A few British and US airmen saw the advantage of strategic bombing in World War I but were unable to convince Army officers in charge of the war to utilize bombing as an offensive strategy, that is, bombing specific non-battle front targets for the sake of military advantage. For US and British Army commanders in the Great War, the fight was on the ground, between the battling foot soldiers. The airplanes main and only responsibility, according to the commanding officers, was to support those troops. If bombs were to be dropped, they would be at or near the battle’s front. Bombing specific targets, such as military production facilities, was not seen as contributing to winning a war. After the First World War, United States airmen continued to push their belief that strategic bombing could impact a war. Their break came, when air force strategists replied to President Franklin Roosevelt’s general inquiry to the US military in the summer of 1941 for best practices for defeating Axis powers, as they expected and planned for the US entry into the current war in Europe.[ref]Birkey, Douglas A. “Aiming for Strategic Effect: The Evolution of the Army Air Force’s Strategic Bombardment Campaigns of World War II.” Dissertation, Georgetown University, 2013. Georgetown University Library, 7.[/ref]

Britain had also began interwar plans for strategic bombing and beginning with their entrance into war in 1939, British air forces began a systematic bombing of German cities. After the United States entered the war in 1941, they added their air force to the British offensive intensifying the bombing efforts the next year. Bombing raids by the Allies were designed to complete two tasks in hopes of shortening the war: weaken soldier and citizen morale, and destroy German war production. As it played out, strategic bombing of key military locations in the European theater worked as planned, causing German military production great problems.

British Bomber Command under Arthur Harris sought total destruction of industrial areas and their associated civilian support as the main objective. While the press and population saw the bombing of German cities as retribution for bombed British cities, Harris saw it as the way to disarm the German military, city by city if necessary.[ref]Childers, Thomas. “‘Facilis Descensus Averni Est’: The Allied Bombing of Germany and the Issue of German Suffering.” Central European History 38, no. 1 (January 1, 2005): 87.[/ref]

Americans approached the issue of bombing with different goals than the RAF. American air strategists, even between the wars, had long studied the problem of bombing in order to determine the most effective strategy. In studying New York city, for example, they learned that the city could be rendered uninhabitable by destroying just seventeen key location. In studying examples of how the Japanese bombed Chinese cities as well as bombing during the Spanish Civil War, American strategists came to the conclusion that terror bombing, or bombing civilians to weaken morale, most often had the opposite effect, and usually led to a much more resistant population. Based on these studies, American strategy was for precision bombing, targeting key industrial and military locations. That American bombing often ended up destroying civilian areas just as much as RAF bombing was due to the limits of technology, rather than conscious implementation of strategy. U.S. operational records and mission reports from raids show that the Americans consistently and honestly, even relentlessly, stressed precision bombing of military and industrial areas.[ref]Childers, Thomas. “‘Facilis Descensus Averni Est’: The Allied Bombing of Germany and the Issue of German Suffering.” Central European History 38, no. 1 (January 1, 2005): 88-89.[/ref]

Differing opinions as to the purpose of strategic bombing caused some tension among British and American air force leaders. American air forces entered the European Theater as a junior companion to the British forces who had already been fighting for two years. While commanders of Eighth Air Force and Eighth Bomber Command were committed to day time precision bombing, and viewed civilian bombing as a waste of resources and inefficient military strategy, they did not want to create more unwanted tension in the British-American alliance. British military leaders pressed their U.S. counterparts to adopt night time raids, citing high casualty rates and the seemingly ineffectiveness of daytime bombing. American air commanders were able to reach concessions at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 by persuading British leaders to adopt an around the clock bombing strategy, with RAF bombing civilian locations at night, and American bombers carrying out raids on military targets by day.